|

|

Manhattan’s Struggle for Human Freedom Against The Slave Power of Virgin

8 May 2015

A Contribution to an Ongoing Discussion by Robert Ingraham EIR—There are myths and counter-myths surrounding the early history of the United States of America. It is often difficult for the mere observer to discern what was actually going on, and what the nature of the battle was. This document will demonstrate that from the very beginning, this nation was defined by a titanic war between two opposing forces, opponents who differed not merely on practical political issues, but on the very nature of the human species itself. On the one side was the New York leadership who created the United States Constitution and defined the mission of the United States during the Presidency of George Washington. Against them were arrayed the Virginia combine of the Southern "Slave Power," an anti-human aristocracy who were determined that it would be the slavocracy of the South who would control the future destiny of the nation. This is the story of that battle. * * * In the years immediately prior to the American Revolutionary War, four young graduates of King’s College (today’s Columbia University) in New York City began a friendship, a personal bond, from which sprang forth the leadership of a new nation. This bond was strengthened and deepened during the years of the American War for Independence, a war which also witnessed the beginning of their intimate relationship with George Washington, and later, in 1787, it would be these four,- Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Gouverneur Morris and Robert Livingston,—who performed the vital role in the creation of the finished form of the United States Constitution, as well as in that document’s successful ratification one year later. Beginning in 1789, three of these individuals—Hamilton, Jay and Morris—would form the nucleus of the leadership in the new Presidential Administration of George Washington, a Presidency whose nature can only be grasped by recognizing that it was a "New York Administration." They were joined and supported by other key New Yorkers, including Steven Van Rensselaer, Philip Schuyler, and Isaac Roosevelt, along with Hamilton’s protégé Rufus King, who moved from Massachusetts to New York at Hamilton’s urging. Later, the legacy of this grouping would be continued through the efforts of DeWitt Clinton, James Fenimore Cooper, and others. Even before the inauguration of Washington, stretching back to the Constitutional Convention and earlier, the philosophy and policy of what would become this 1789 New York Administration was ruthlessly and bloodily opposed by the Slave Interests of the South. There are two related delusions concerning slavery and the American Republic. The first is that the founding fathers were either pro-slavery, or at least tolerant of that institution. The second is that slavery did not emerge as a decisive national crisis until the 1830s or 1840s, or until the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. The truth, is that beginning with the inauguration of George Washington in 1789, war was declared against that Administration by the Slave Power, and beginning with the election of Thomas Jefferson in 1800, the Southern Slave Power unleashed a relentless, unceasing effort to increase its power, expand geographically and ultimately take over the entire nation.

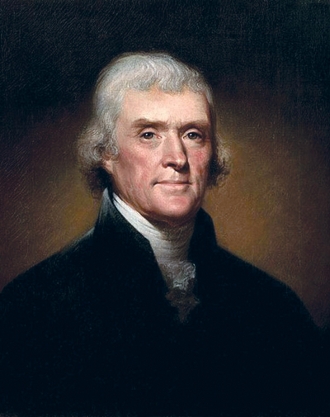

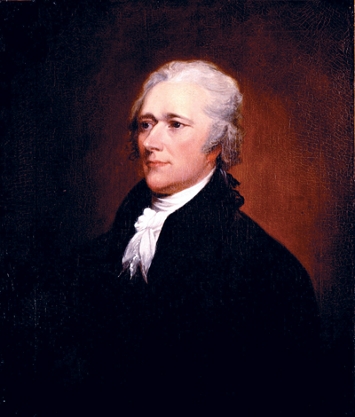

The protagonists. On the left, Rembrandt Peale’s 1800 portrait of Jefferson; on the right, John Trumbull’s posthumous portrait of Hamilton.More was at stake than simply the institution of slavery. The first Washington Administration was an experiment as to whether the principles of the new American Constitution, a constitution steered to its completion by New Yorkers, might succeed in practice. It was the Administration of Alexander Hamilton’s creation of a National Bank, and Hamilton’s formation of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures. The Washington Presidency was the battleground for the creation of a type of Republic never before existent in human history. From the beginning, the mortal enemy of this design was the Slave Power of the South. Part I: The BeginningsJohn Jay and Robert Livingston met as students at King’s College in the mid-1760s, and they became the closest of friends until their break in 1792-1794. Within a few years Gouverneur Morris was part of their group, and this trio was to provide the revolutionary leadership for New York State during the ensuing decade. Hamilton, the youngest of the group, was a slightly later addition, but it was this final arrival whose destiny was to be the greatest of them all. All four emerged from, or were linked to a network of prominent New York families, including the Livingstons, Van Rensselaers, Schuylers, and Morrises. Alexander Hamilton and Steven Van Rensselaer both married daughters of Philip Schuyler, and John Jay married one of the daughters of Walter Livingston.

During the Revolution, not only did Hamilton serve as Washington’s most trusted aide, but it was Jay, Livingston, and particularly Morris who became Washington’s most vigorous defenders in the Continental Congress. Morris and Livingston defended Washington against repeated attempts to remove him from command,[1] and throughout the war, no one fought harder than Morris to secure food, ammunition and medical care for Washington’s troops.[2] It is vital to recognize that to a very real extent, the leadership of the later Washington Presidency was forged, so to speak, over the "campfires of war," by individuals who served directly with Washington during that conflict, including Hamilton, Gouverneur Morris (who spent four months with the army at Valley Forge), Henry Knox (later Washington’s Secretary of War), John Marshall (also at Valley Forge) and Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee. These individuals, together with others not named here, remained unassailable in their loyalty to Washington until the moment of his death. In 1774, after the British government closed the Port of Boston, a committee is formed under John Jay’s leadership, to organize a new revolutionary government for New York State: the New York Provisional Congress. Morris and Livingston are elected as representatives to the new legislature, and Jay is the first delegate chosen to the new Continental Congress in Philadelphia. In 1776, the New York Provisional Congress, at the urging of Jay and Morris, authorize their representatives in Philadelphia to vote for independence. Livingston serves on the Committee of Five, together with Ben Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Roger Sherman, and John Adams, which drafts the final version of the Declaration of Independence. Later that year Jay and Morris author a new constitution for New York State, and elections are held to form a new state government. Jay is elected Chief Justice, Livingston is elected Chancellor, and their ally Philip Schuyler is barely defeated for Governor by George Clinton. From 1781 to 1783, Gouverneur Morris, together with Robert Morris, are the vital leaders in reorganizing the nation’s finances and staving off national bankruptcy, and, together, they found the Bank of North America. John Jay, from 1779 to 1782, serves as Ambassador to Spain and then, at the request of Benjamin Franklin, proceeds to Paris to aid Franklin (whose efforts are being sabotaged by John Adams) in securing the final peace treaty which ends the war. Part II: The ConstitutionA continuing lie surrounding the United States Constitution is that Alexander Hamilton played a minor role at the Constitutional Convention and had little input into the final document. The truth is that there would have been no Constitution without Hamilton. He was the initiator of the project and, almost single-handedly, responsible for the convening of the Convention in the summer of 1787; and, afterwards, Hamilton was the driving force for ratification in 1788. In addition, he intervened in two crucial and decisive ways at the Convention itself. Hamilton’s campaign from 1783 to 1787 to replace the Articles of Confederation is well-known, and the details will not be repeated here, except to emphasize his role in initiating the Annapolis Convention, which met on September 12, 1786 and ended two days later with the Hamilton-authored "Annapolis Resolution," calling for the convening of a national convention in Philadelphia in May of 1787, to be attended by all the states. This was Hamilton’s project from the beginning.

The Philadelphia Convention opened with the presentation of the "Virginia Plan," a document which emanated from James Madison. Madison’s proposal was a mess, particularly in the extreme weakness of the Presidency and the Judiciary, and the extensive power it granted to the individual state legislatures. More important, the Madison plan had no intent; it was merely a social contract. Even worse, the Virginia proposal was followed several days later by the presentation of the "New Jersey Plan," a rewarmed version of the Articles of Confederation. The grim choice between some version of these two bad alternatives would have been inevitable, but, on June 17, 1787, Hamilton met with George Washington and convinced him to turn over the entirety of the next day’s agenda to only one speaker, Hamilton himself. On June 18th Hamilton spoke, uninterrupted, for six hours, presenting his own vision for the new government. Historians almost universally deride this intervention, calling Hamilton’s proposal the "British Plan" (despite the fact that it bears no resemblance whatsoever to the British government), and claiming that his speech had no support and little effectiveness. On the contrary! Through his sheer will and the brilliance of his argument, Hamilton transformed the entire nature of the gathering. From the moment of Hamilton’s speech, the New Jersey Plan died, and the nationalists gained the ascendency in the Convention. The battle then became one to improve upon the Virginia Plan, to transform it into the basis for a sovereign Republic. Shortly after his speech, Hamilton left the Convention for most of the rest of the summer. Again, historians point to this as evidence of Hamilton’s pique at the supposed lack of support for his proposal, but a major reason that Hamilton absented himself from most of the convention, was due to his status. New York State had sent three delegates, but two of them, allied with George Clinton, withdrew when they discovered that the Convention intended to overthrow the Articles of Confederation. Without them the New York delegation did not have a quorum, and thus lost its vote. Hamilton’s official position had been reduced, according to the rules of the Convention, to that of a mere observer. This is why, at the end of the Convention, Washington stated that the Constitution had been signed by "11 states and Col. Hamilton," New York not having a valid vote, and Rhode Island boycotting the Convention. After Hamilton’s departure, it was Gouverneur Morris who led the battle against States’ Rights and Slavery at the Convention. More than any other individual, it was Morris who was responsible for the clauses creating a strong Presidency—the American Presidential System—and it was Morris who battled, almost alone, against the institutionalized Slave Power of the South. During the Convention, Gouverneur Morris roomed with Washington at the home of Robert Morris, and it was very clear to all of the delegates that when Gouverneur Morris spoke,- and he spoke more often than any other delegate at the Convention,- the views he propounded were sometimes his own, but often those of Washington as well. This is what Hamilton and Morris together accomplished: 1. First, the establishment of a strong, independently-elected’ Executive, through the Office of the Presidency. Morris was unsuccessful in his attempts to establish a full democratic popular election of the President,[3] but he and Hamilton were successful in preventing the selection of the President by either the Congress or the State Governments, which were the majority views at the beginning of the convention. They also were able to empower the President with broad executive powers. 2. The inclusion of a broad General Welfare clause, both within the body of the Constitution, and more importantly the Morris-authored Preamble, which charges the National government to protect and defend the General Welfare for future generations. 3. The establishment of a strong independent Judiciary, something which later became a major source of conflict with the Jeffersonians. 4. Morris and Hamilton were the most eloquent champions of nationalism at the convention,—particularly Morris, who spoke repeatedly and passionately as the champion of national unity. He attacked states’ rights and localism from every angle and at each time it reared its head. 5. Morris led a critically important fight over slavery at the convention. Practically alone, he waged this fight all the way through to the closing hours of the convention, brilliantly and uncompromisingly. The Three-Fifths clause which vastly inflated the national political power of the slave states was adopted against Morris’s intense opposition. At the conclusion of the Convention, a "Committee of Style and Arrangement" was appointed to write the final draft of the Constitution. The chairman of the committee was Hamilton, and both Gouverneur Morris and Rufus King were members. This Committee did not merely "polish" the final wording of the Constitution. They were given a hodgepodge of individual clauses that had been approved by majority vote, and their instructions were to arrange them into a unified composition. In doing this, nothing that had been already approved was changed, but the wording and phrasing of the final document all derived from the Committee, and, repeatedly, the emphasis in the final document is such as to strengthen the truly national character of the new government. Among other things, they clarified the General Welfare clause, and they made significant changes to Article III which strengthened the Federal Judiciary. The great history-changing accomplishment of Hamilton’s Committee, however, was its addition of the Preamble to the Constitution. All contemporary witnesses agree that it was Gouverneur Morris who personally authored the Preamble, thus giving the entire document its philosophical intent. Reportedly, some of the delegates, upon receiving the completed Constitution from the Committee on Style, were unhappy with a Preamble they had neither asked for nor authorized, but it remained, unchanged, in the final document. When you read the words,

you are reading not only the words of Gouverneur Morris but the Principle which he, together with Hamilton, embedded in the founding document of our nation. Morris vs. the Slavocracy The great untold story of the Constitutional Convention is that the slave interests of the South, led by Virginia, were determined and unyielding that the final agreement would lead to a domination of the new nation by the Slavocracy. Their power and their system was to be enshrined, with legal finality, in the founding document of the nation. This included their demands for enhanced political power based on their states’ total slave population, for no restrictions to be placed on the slave trade, for no restrictions on the expansion of slavery into the territories, and for the use of various clauses in the Constitution dealing with property rights to protect slave ownership.

James Madison’s original Virginia Plan called for one-to-one representation of the slaves for the purpose of determining an individual state’s number of Representatives in the Congress, as well as that state’s number of Presidential Electors. For example, in 1790, Virginia had 435,000 free inhabitants and 300,000 slaves, while Pennsylvania had 434,000 free inhabitants and no slaves. Under the Madison Plan, Virginia’s representation would be based on 735,000 people. They almost got away with it, but there was enough opposition among some of the northern delegates, that on June Eleventh (when Gouverneur Morris was absent from the Convention), James Wilson of Philadelphia proposed the Three-Fifths "compromise," allowing the South to count 60 percent of their slaves towards representation. This would, for example, allot to Virginia representation for 615,000 "people." Wilson’s proposal was adopted with eight states voting for it, and two (Delaware and New Jersey) opposed, and that is where matters stood for one month. On July Eleventh, Gouverneur Morris rose to speak at the Convention to re-open the already-decided issue of the Three-Fifths clause. The record of his speech and the ensuing lengthy debate with James Wilson is not preserved, but it must have been effective, for at day’s end, the Convention voted six states to four to eliminate the Three-Fifths clause and to award no representation for slaves. However, the fight was not over, and during the next two days there were heated exchanges, with only Morris repeatedly taking a strong anti-slavery position, in the face of Southern threats to walk out of the convention. On July Thirteenth, another vote was held, and the Three-Fifths clause was reinstated, with the Southern concession that Three-Fifths of the slaves would be counted for both representation and direct taxation. The vote to reinstate the Three-Fifths clause was six to two, with two abstentions. Morris was the only member of the Pennsylvania delegation[5] to oppose the compromise. Morris was not yet done. On July 24th he delivered yet another speech demanding that the Convention revisit and remove the Three-Fifths clause. Incredibly, the five-person Committee on the Whole, in response to Morris’s intervention, then voted to reinstate full one-to-one representation (!) for slaves. On August Eighth, when no other delegate was willing to openly defy the ultimata of the Slave Power, Morris rose and faced the entirety of the assembled delegates. He said the following: Upon what principle is it that the slaves shall be computed in the representation? Are they men? Then make them citizens and let them vote. Are they property? Why then is no other property included? The houses in [Philadelphia] are worth more than all the wretched slaves that cover the rice swamps of South Carolina.... The admission of slaves into the representation when fairly explained comes to this: that the inhabitant of Georgia and South Carolina who goes to the coast of Africa and, in defiance of the most sacred laws of humanity, tears away his fellow creatures from their dearest connections and damns them to the most cruel bondages, shall have more votes in a government instituted for the protection of the rights of mankind, than the citizen of Pennsylvania or New Jersey who views with laudable horror so nefarious a practice.... Domestic slavery is the most prominent feature in the aristocratic countenance of the proposed Constitution. The vassalage of the poor has ever been the favorite offspring of aristocracy. And what is the proposed compensation to the Northern States for a sacrifice of every principle of right, of every impulse of humanity? They are to bind themselves to march their militias for the defense of the Southern States; for their defense against those very slaves of whom they complain. They must supply vessels and seamen in case of foreign Attack.... On the other side, the Southern States are not to be restrained from importing fresh supplies of wretched Africans... nay they are to be encouraged to it by an assurance of having their votes in the National Government increased in proportion, and are at the same time to have their exports and their slaves exempt from all contributions for the public service.... Slavery is a nefarious institution, the curse of heaven on the states where it prevails. Compare the free regions of the Middle States, where a rich and noble cultivation marks the prosperity and the happiness of the people, with the misery and poverty which overspread the barren wastes of Virginia, Maryland and the other States having slaves. Travel through the whole Continent, and you behold the prospect continually varying with the appearance and disappearance of slavery. The moment you leave the Eastern States and enter New York, the effects of the institution become visible,—passing through the Jerseys and entering Pennsylvania, every criterion of superior improvement witnesses the change. Proceed southwardly and every step you take through the great region of slaves presents a desert increasing, with the increasing proportion of these wretched beings. At the conclusion of his speech, Morris proposed one small editorial change: to insert the word "free" before the word "inhabitants," which would, of course, have eliminated all slave representation. Morris’s motion was overwhelmingly rejected, but in the aftermath of the speech, the Convention voted to reinstate the Three-Fifths representation instead of the Committee’s one-to-one proposal. This vote effectively ended the debate over slave representation. The slave trade was debated from August 21st to 28th. South Carolina led the fight in demanding an unrestricted slave trade. Morris counterattacked, speaking repeatedly, even at one point proposing—as a provocation—that the constitution prohibit the slave trade, but that Virginia, Georgia, and South and North Carolina be exempted due to their commitment to "human bondage." This caused a furor on the convention floor. Eventually, James Wilson proposed another compromise, one allowing the slave trade to continue for 20 years and imposing a head tax on imported slaves. Morris spoke sharply against it, but it passed. The effect of this "compromise" was that over the next 20 years, from 1790 to 1810, 203,000 slaves were brought into the United States, compared with only 56,000 in the previous 20 years. The last slave-related issue was that of run-away slaves. The Convention had already agreed to a clause requiring Governors to surrender criminals for extradition to other states, but on August 28th the South Carolina delegation demanded that fugitive slaves must be included in the definition of criminals. Wilson again proposed a "compromise," whereby slaves would not come under legal extradition agreements, but slave-owners would have the legal right to enter into other states (or hire someone to do this for them), and seize their run-away slaves, i.e., recover their rightful property. This was the origin of all later "fugitive slave" laws. Again, Morris was vehement in his opposition, but it was voted up by the convention. The Philadelphia Convention ended with the proviso that the new Constitution would go into effect only after it had been ratified by nine states. Hamilton initiated the fight for ratification with the publication, on October 27, 1787, of the first of what later would become known as the Federalist Papers. Hamilton initially intended his political offensive to be a two-man operation run out of New York City. At the outset he asked Gouverneur Morris to join in authoring a series of essays, but he declined due to prior obligations to Robert Morris in Philadelphia. Hamilton then turned to John Jay, but after Letter Nine, Jay was forced to withdraw because of bad health. Hamilton then chose William Duer, another New Yorker, as his collaborator, but ended up rejecting Duer’s submissions as inadequate. It was only then that Hamilton turned to Madison, his fourth choice, to aid in writing the series. Over the course of 1788, there were several key battleground states in which ratification was in doubt, including New York, Massachusetts and Virginia. In Massachusetts it was Rufus King and Henry Knox who played the key roles in winning over the leery John Hancock and Samuel Adams to ratification, but the fight in New York was the most intense. For well over a month, during the summer of 1788, a ratifying convention was held at Poughkeepsie, New York, and until the final days, ratification was uncertain. The majority of the delegates, under the direction of Gov. George Clinton,[6] were opposed to ratification, but the delegation from Manhattan, which included Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, Robert Livingston, and Isaac Roosevelt, battled ferociously until ratification was secured in late July.[7] At the end of the summer, the Continental Congress declared the Constitution to be lawfully ratified, and named New York City as the temporary seat of the government. It was not inevitable that Washington would head the new government. Following his service in the French and Indian War and the American Revolution, Washington had informed many of his associates of his desire to retire from politics. Hamilton and others knew that a Washington Presidency was indispensable to what had to be done next. Neither Hamilton nor any of his close associates were happy with the final Constitution, but as Morris was later to describe the finished document, "it was the best that could be accomplished ... and infinitely better than the existing Articles of Confederation." The task now was to bring the words on the page to life, and to utilize all of the powers granted by the Constitution to secure the permanent continuance of a sovereign republic. To accomplish that, Washington was urgently needed. Hamilton, Jay, Morris, and Henry Knox all communicated directly with Washington, expressing their belief that the historic mission could not be completed without his leadership. Morris wrote, "Should the idea prevail that you would not accept the Presidency, it would prove fatal to ratification in many Parts... your cool steady Temper is indisputably necessary to give a firm and manly Tone to the new Government... you therefore must, I say must mount the Seat. The Exercise of Authority depends on personal character, and you are the indispensable man." Three weeks after authoring that letter Morris traveled to Mount Vernon and spent three days in private discussion with Washington. Washington was duly elected, and on April 30, 1789, in Manhattan, he was sworn in as the first President of the United States, Robert Livingston, the Chancellor of New York, delivering the Oath of Office. Washington was the man in charge, and his word was final, at least to his friends and allies, but, from the beginning, it was Hamilton to whom Washington turned for policy leadership. Washington was not a "figurehead," but he recognized in Hamilton that genius necessary for the establishment of the new Nation, and Hamilton’s role in the government became so pronounced, so quickly, that Jefferson and his allies began to denounce New York City, the Capital of the Nation, as Hamiltonopolis. This article appears in the May 8, 2015 issue of Executive Intelligence Review. |